As far as I can remember, this is only the second Neal Stephenson book I’ve read. The first was Snow Crash. As you’d expect from books written twenty years apart, they’re quite different. From this admittedly tiny sample size, I get the impression that Stephenson has undergone the same transformation as William Gibson, from cyberpunk science-fiction to stories that interpret current technology through a futurist lens: stories that say, ”it’s hard to believe it, but these things could happen today.”

Reamde is a book about ransomware, money laundering through MMORPGs, the Russian mob, and Islamic terrorists in China.

1. Style is an Engine of Story

Sentence-to-sentence, Reamde is a fantastically well-written book. Stephenson’s prose reminds me of literary fiction, because it was just as critical to my enjoyment of the book as the characters or plot. However, the style is very different. It’s not lyrical, it’s clean and precise, but that doesn’t make it any less captivating.

The best way I could describe it is that it feels like walking through the story with Terminator vision—everything overlaid with little details, and targets zooming in to focus your attention on important things.

There are many engines that can power a story, and a strong style like this is a great one, if you can manage it. Since it’s all about how you say it, not what you’re saying, it layers nicely with other engines.

2. Eschew Unnecessary Detail

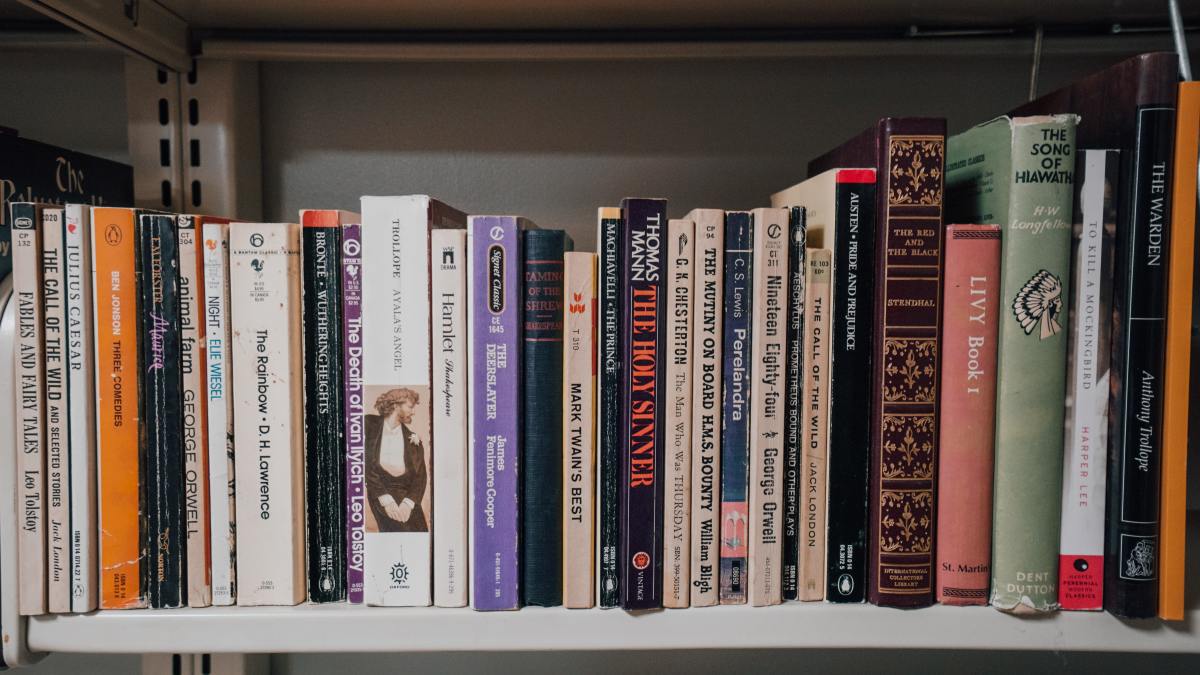

The level of detail used to describe something—a place, a character—can be an important cue to the reader. Describing something in detail indicates its importance, and explicitly limiting that detail shows a lack of importance.

At one point in the book, some characters meet the pilots of the private jet they will be riding on. The pilots’ introduction is sparse: “He greeted the pilot by name.”

The pilots are necessary to the plot, so they have to be mentioned. Stephenson could have come up with a throw-away name, but this gets across the message just as well. It’s a clue that the pilot will only be relevant for a short while. The reader doesn’t have to worry about remembering the name of yet another side character.

When characters are going to be important (or at least stick around for a while), Stephenson makes sure to introduce them in a way that reveals one or two interesting physical characteristics and something that reveals a bit of their personality. This makes them instantly memorable.

The other great use of this technique is to add detail to accentuate things that will be important to the plot. It’s like a miniature “gun on the mantle.” If you spend time describing a key and a padlock, that lock ought to be important. If you leave garbage out in the forest to attract dangerous animals, some dangerous animals had better show up at some point.

3. Coincidences Strain Believability

Incredible coincidences or lucky breaks aren’t unusual in action/suspense stories like this, but they have to be used carefully.

Reamde’s plot really kicks off with one such coincidence, and it results in several characters getting mixed up with the Russian mob. To me, a crazy coincidence works great as an inciting incident.

Where coincidences start to chafe is when they’re used to repeatedly ratchet up the tension, or even worse, to resolve a problem.

There’s an egregious example of this at the end of Act I of Reamde, where everything that happens in the latter 2/3 of the book hinges on a group of hackers who just happen to live in the same run-down tenements as a terrorist cell. In a city of millions.

There are other examples as well, including several chance meetings among the large cast of characters that end up being vital to the plot later on, and many of the characters being players of the in-story MMO, T’Rain, so that there’s always someone available to log on when it becomes relevant to the plot again.

When I got to the part where bad guys were killed by a cougar, I had to stop reading and look up the stats on cougar attacks. Then I just threw up my hands and accepted that this is what I signed up for. That’s not the kind of reaction you generally want from a reader.

4. Beware Pet Characters

Stephenson is deeply in love with Richard “Dodge” Forthrast. He’s the cool, smart guy who gets along in any social strata and knows all the things. He’s a former pot smuggler turned Silicon Valley CEO. He’s bored of being a billionaire, because he’d rather be out solving some new earth-shattering problems. He is the Golden Boy caricature that people like Musk, Zuckerberg and Bezos try to project.

Even in a life-threatening situation, he’s having fun, practically on vacation. It’s really only at the very end of the book where he shows any amount of fallibility. Of course, he makes up for it by being the guy who saves the day.

The strangest thing of all is that this is really not his story. Although the perspective jumps around, the bulk of it is from the perspective of Zula, his niece, and she’s the one with a character arc and the most to lose. Yet the story starts and ends with Dodge.

Because Stephenson is a great writer, Dodge is still a fun character, but I’d like him more if he was a little more human and fallible.

5. Structure is a Double-Edged Sword

Like most suspense stories, Reamde has constantly escalating stakes. Every section is essentially “out of the frying pan, into the fire.” Things could always get worse (or worse in a new way).

The danger of this constant escalation is that it can quickly ramp to extremes (and well beyond). It’s easy to jump the shark.

In Act II, Reamde splits many of the characters up into separate groups in their own bad situations. I realized pretty quickly that the rest of the book was going to be about how everyone long journey to end up back together in one place, for the final showdown.

However, wrangling everyone back to the same place, at the same time, requires introducing another round of characters and another handful of helpful coincidences.

This made the second half of the book feel considerably more meandering. When everyone finally arrived at the final showdown, there were so many characters involved and so much to resolve that there were literally 100 pages of running gunfights.

By that time, the story had escalated to such extremes that my reaction to the bad guy’s final defeat was a combination of exhaustion and relief that it was done.

Bookends

It’s been a while since I read a book that was such a mix of joys and irritations. I love Stephenson’s prose, but this book did not need to be a thousand pages or finish with a novella-length series of shootouts.

Reamde was released in 2011, so I’m thinking I’ll pick up Stephenson’s latest novel, Termination Shock, sometime soon, just to get the full “bookend” experience of his career so far.