It’s a new year. I’m working on the pile of books and comics I got for Christmas, and mostly ignoring the books I had planned to read. Someday I’ll get back to The Witcher. Someday.

If any of these sound interesting, please use my bookshop affiliate links instead of Amazon. I’ll get a small commission, and you’ll support real book stores instead of phallic rockets for billionaires.

Signal to Noise

By Neil Gaiman and Dave McKean

I thought I had read nearly all of the Gaiman/McKean comics collaborations, but this one somehow slipped under my radar. Published in 1989, Signal to Noise is almost a prototype of their future work. It’s a little less subtle with its themes than later works, but it still shows that expertise at crafting a story that can be observed from a dozen different angles to reveal some new through-line or idea.

The “noise” cutting through the signal of the story is nonsensical text, hinting at meaning without ever finding it. At the end of the book, it’s explained that this text was produced by a text sampler program, a 1989 prototype of the LLMs that have recently become so prevalent.

McKean’s illustrations are a fever-dream. The filmmaker inhabits a foggy ghost world. The movie in his head is unfocused and clogged with snow. Pops of color cut through: the yellow of a wheel clamp on an illegally-parked car, a red traffic light, a rare splash of green from a potted plant. The story is drowning in monochrome blue-white-gray, and the splashes of color are quick breaths before going under again. The panels shift between purposely similar 4×4 squares (evoking strips of film) and luscious full-page spreads, especially potent in this oversized form-factor.

The main character is a filmmaker, who is dying. He’s composing a movie in his head: people in the year 999, waiting for the new year, when they expect the world to end. A dying man composing a story of the apocalypse. But the apocalypse never came for those people.

For me, the resonating theme of the book is creator’s remorse. The work, when done, is never as good as it was in your head. But there is always hope that the next piece will be the one that works. Still, there is joy in it. A finished piece of art evokes “the feeling that one has clawed back something from eternity, that one has put something over on a nodding god, that one has beaten the system.”

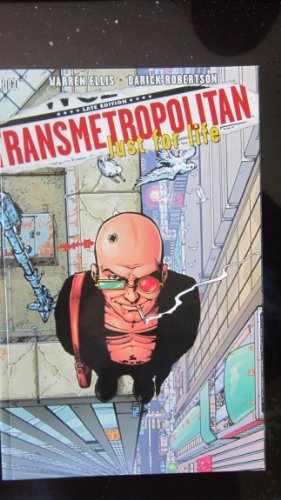

Death: The High Cost of Living

By Neil Gaiman and Chris Bachalo

Continuing the theme of old Gaiman comics, we have short spin-off in the Sandman universe, starring the effervescent goth girl Death, possibly the most popular of the Endless, apart from Dream.

Once each century, Death must spend a day as a mortal, and this just happens to be that day. She meets a boy named Sexton, who happens to have written a suicide note he has yet to act on. He is utterly disillusioned with the world, as only an inexperienced teenager can be.

Death, going by Didi today, explains who she is and invites Sexton to spend the day with her. He does , complaining all the way, and only slowly coming to believe Didi really is the personification of Death.

The magic of the Sandman version of Death is that she knows everyone, and she loves everyone, regardless of how the average human might judge them. She embodies the Christian ideal of kindness that many people aspire to, and none really achieve. So, of course, she goes on a little adventure with Sexton, and it changes him. He gains a new outlook on life. I won’t spoil who ends up dying at the end.

If you like the Sandman universe, this is a fun little jaunt along the edges of it, with a few familiar faces, and a good story in its own right.

Persepolis

By Marjane Satrapi

Persepolis is autobiographical history in the comic tradition of Maus. The author grew up in Iran, living in a well-off family of intellectuals.

The first part of the book is largely about Satrapi’s childhood, and the many revolutionary elements that led to the overthrow of the Shah, followed by the disappointment of groups like the communist revolutionaries when the movement was hijacked by Islamic fundamentalists.

In the second half, Satrapi moves overseas, attends college in Germany. She gets into drugs, spends time homeless, and manages to rebuild her life. After her time abroad, she returns to Iran and finds herself chafing against the rules of the regime.

She finds a boyfriend and marries, but they are almost immediately unhappy. The end of the book is abrupt. She gets a divorce and moves overseas again, this time to France.

Although it’s sometimes disjointed, the book is a great ground-level introduction to the recent history of Iran and a culture that I certainly didn’t learn much about, growing up in America.

There seems to be an inherent dissonance in Iranian culture between public and private life. Despite Islamic theocracy, many Iranians hold on to Persian culture, seeing themselves as independent from the rest of the Middle East. The fundamentalist regime makes the consumption of alcohol and mixed-gender parties illegal, but they still secretly happen with regularity. Head coverings are mandatory and makeup is frowned-upon, but many women flout these rules, even in public when they think they can get away with it. Punishments for breaking these cultural rules can be avoided by paying a fine, which results in the wealthy having much more leeway than the poor.

While it might be cliche, the obvious takeaway is that Western countries have more in common with Iran than the uneducated (like me) might think. There is a thread of fierce personal independence and self-determination in these stories that will feel familiar to anyone who has grown up in America, as will the rifts between social classes and the mismatch between public perception and private reality.

Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix

By J.K. Rowling

The Potter read-through with my kids continues. It’s the fifth book in the seven-book Potter series, and everything’s falling apart. Wizard Hitler is back in town, consolidating power in secret. Meanwhile, the government refuses to believe the only evidence: the eyewitness testimony of our 15-year-old protagonist.

As a series of kids’ books, I’m willing to overlook some of the simplicity of world-building that a lot of folks like to harp on, but this book really makes it clear how dysfunctional the “wizarding world” is. There are a great many institutions that are unique in the wizarding world, and that makes it awfully easy to gain and abuse power.

There’s effectively only one wizard newspaper. The government apparently exerts tremendous control over it, and can just squash articles they don’t like. Harry only gets his story published in a homemade conspiracy zine.

There’s a very simple wizard government, with a single head of state that seems to have total control over the unicameral legislature. In fact, it’s not even clear if anyone except the wizard president even needs to sign off on new laws.

There’s a single, hellish maximum-security wizard prison, which seems to be the default punishment for any non-trivial offense. There’s a single wizard bank, just in case the all-powerful government wants to exert economic controls as well. Finally, there’s only one wizard school in the country, so it’s nice and easy to lock down that educational system.

The wizarding world is a model autocracy. No wonder a new wizard Hitler crops up every couple decades.

Anyway, this book marks Harry at his most persecuted. The all-powerful government hates him because he keeps saying that Voldemort is back, and exerts all its power to convince everyone he’s a crazy person. His friends are mostly children, so they can do very little about this. The few adults on his side have created a secret society to try to fight back, because they’d be targets for the all-powerful government if they were open about it.

The theme of being unable to depend on adults really reaches its peak here. The school is taken over by a sadistic pawn of the government, the adults who Harry trusts are picked off one-by-one, and even Dumbledore, who has always been a bit like Old Testament God (distant, but loving authority figure), purposely abandons Harry.

As usual, Harry leads the kids by ignoring all adult advice and doing what he thinks is best. On the one hand, this is a pretty bad idea because he knows full well that all the adults have been hiding a lot of information from him. He doesn’t really know what’s going on. As usual, he’s ignored their warnings. On the other hand, this has worked out well for him in every single book up to this point. Maybe if the adults wanted him to behave, they should have tried a little harder to parent the headstrong super-wizard orphan boy.

Where previous books like Prisoner of Azkaban toyed with the idea that Harry’s poorly thought-out actions might cause real problems, everything always turned out prefectly when he followed his gut. Even the first death of the series in Goblet of Fire was not really his fault. He got played by an adult he trusted. But in Order of the Phoenix, Harry lets his intuition guide him, against the advice of literally everyone, and the result is terrible.

Sure, they get incontrovertible evidence that Voldemort’s back. So that’s nice. It just costs the life of the only person Harry considers family.

There is also a problem of Harry’s personality in this book. He’s constantly angry, and generally mean to all of his friends. In the end, it turns out that he’s being psychically manipulated, but there really aren’t enough hints about what’s going on, so he just comes across as an unpleasant character for most of the book.

Consider This

By Chuck Palahniuk

I won’t harp on this one, since I’ve already written a separate post about it. Suffice to say it’s the best book on writing that I’ve read in a few years.

What I’m Reading in February

Harry Potter continues. I’m halfway through a beautiful hardcover complete edition of the comic Die. I may dig into a stack of anthologies, to stay on-brand for my year of short stories. And there is always the eternal promise of jumping back into The Witcher. It could happen.

See you in February.