…just days after I finished posting Razor Mountain.

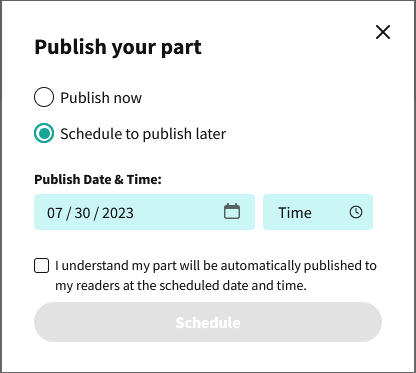

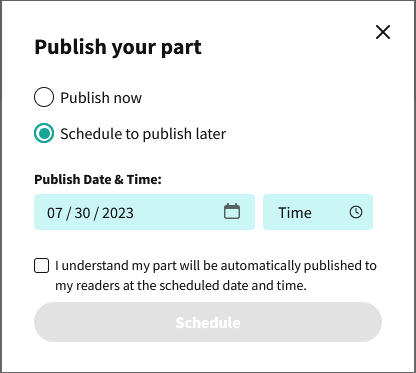

This was a seriously overdue change, and hopefully it’ll be good for all the writers with stories in progress. I sure would have liked to have it for the past two years.

…just days after I finished posting Razor Mountain.

This was a seriously overdue change, and hopefully it’ll be good for all the writers with stories in progress. I sure would have liked to have it for the past two years.

This weekend, while mowing the lawn, I listened to Asphalt Meadows, the new Death Cab for Cutie album. I am a horrible screen addict who has to constantly fight the urge to inundate myself with multiple streams of content at once, Back to the Future-style, so mowing the lawn is a great time for me to actually listen to music while part of my brain is focused on the simple task of driving in straight lines.

Upon initial listen, I really liked it. It’s clearly recognizable as a Death Cab album, but it also feels like something very different from the band. There is considerably less slick production. The sound is much more raw. Out of the quiet parts, they blast you with almost violent noise.

Death Cab has always had an emo melancholy streak, but it’s amped up here. And yet, there are still glimmers of hope in the face of tragedy. I’m hardly an expert music critic, but it feels like a Covid album.

The last few years have had such broad effects on society and on most of us personally. I’ve been wondering for a while just what long-term changes this will wreak on the world at large. It’ll take decades to begin to understand how these plague years have changed us.

As a writer, I think one of the most interesting lenses to view society through is our stories. There are always trends in fiction, like the waves of zombies following The Walking Dead, the vampire romances following Twilight, and the myriad dystopias post-Hunger Games. But there are bigger trends too. These meta-trends can show something about our collective sentiment or what we’re seeking in our imagined worlds that we feel lacking in the real one.

The optimistic science-fiction of the post-WWII era reflected a society that thought it could do anything. This was a society that believed technology could be harnessed to solve any problem and overcome any obstacle. This was the Jetsons-style future of sleek silver spaceships and moving sidewalks and personal robot butlers.

When this blog was young (a whopping 1.5 years ago), I wrote an article inspired by a tweet by William Gibson, and asked, is cyberpunk retro-futurism yet? Looking back, I think that while the aesthetics of cyberpunk have been reused and recycled extensively, it’s the deeper themes of cyberpunk that really seem to be oddly on-point in our current day and age.

The futurists of the 1980s looking toward a world dominated by mega-corporations and invasive technology seems almost quaint in our modern era of Amazon and Facebook, of ad-targeting and bot-farms and Cambridge Analytica and wondering whether Alexa or Siri is listening in on our conversations. In a lot of ways, we’ve out-cyberpunked the genre of cyberpunk with our own dystopic reality.

But looking beyond these surface-level themes of cyberpunk, I think there is an even more resonant core. Cyberpunk is about vast, uncontrollable systems. Rogue AIs, mega-corporations, and legions of near-human replicants all represent systems so big and so complicated that the average person on the street has no way to even understand what’s going on, let alone take it in a fair fight. Cyberpunk is about survival in a world of vast, incomprehensible, world-controlling systems that are completely indifferent to you.

Surviving in a completely indifferent world. Boy, that sounds familiar.

What about the last few years? What has changed in our stories? Again, this is something that will need the space of another decade or two to really understand, but I can look at the anecdotal evidence of the stories I’ve been reading and watching recently. A lot of these stories are about found family, about belonging, hope and love in a world of hate and nihilism.

Covid, along with the political and cultural fissures that have developed and deepened in recent years, have left many of us feeling…brittle. The world is made of glass these days. It feels like so many things are just barely holding together, and it would only take one or two well-aimed blows to shatter. This is what I heard in Asphalt Meadows while I mowed the lawn.

If the era of The Hunger Games and its dystopian facsimiles was about fighting back against authoritarianism, this era of fiction feels like an all-out fight against nihilism. Only, back in The Hunger Games days, there really wasn’t anyone rooting for the authoritarians. (If anything, people were awfully glib about the message of that series, which seemed to be that it’s not actually that easy to make things better through violent revolution.)

Today’s question seems to be whether or not to give in to complete nihilism, and I think the jury is still out on which way we’re going.

One of the best movies of the past year was unquestionably Everything Everywhere All at Once. If you haven’t seen it, go see it right now. If you have seen it, go watch this great analysis on Movies With Mikey (one of my favorite channels about movies), and feel those feelings all over again.

E.E.A.A.O. puts to shame the shallow multiverses of Hollywood powerhouses like Marvel. This isn’t an excuse to trot out all the nostalgic reboots of reboots of reboots. This isn’t a story where evil threatens to destroy the world, or even the universe. This is a threat to every world in every universe. You know, everything everywhere all at once. Only, the threat isn’t evil. It’s malicious indifference. It’s nihilism.

In the absurd drama that only The Daniels can pull off with such panache, it’s the literal “everything bagel,” the black hole of indifference that threatens to absorb the sprawl of infinite universes. After all, when the universe is infinite, everything that can happen, happens. Nothing is unique. Nothing is special. In the face of everything, nothing matters. This is the argument the characters of the film are pitted against. Why care? Why bother?

Despite all the universe-hopping and existential threats, this isn’t really a movie about big stakes. Big stakes are what fuel nihilism. It’s those incomprehensibly huge cyberpunk systems that can’t be fought by mere mortals. Like Amazon and Facebook, or national US politics. This is a film about the opposite of nihilism, something I’m not sure there’s even a good word for. Perhaps it’s along the lines of the Buddhist idea that when nothing matters, everything matters: every word, every action, every choice and every moment has value.

The movie centers around the moment when the protagonist begins to understand this. She stops worrying about the fate of everything everywhere, and starts paying attention to the people around her: her husband, her daughter, her father, her IRS auditor. She stops worrying about the incomprehensible systems and the vast universe that seem like the overwhelming problem, and focuses on what she can do in the here and now. She fights nihilism with hope, and (perhaps because it’s a movie) that’s what saves the multiverse, and more importantly, her family.

Even as I write this, I have a hard time taking myself seriously. Determined hope vs. nihilism, what a unique and clever new idea, right? Spoken plain, it feels a little too simple, even childish. But then I look at the fragile world around us, and at my own perpetual temptation to look at no less than two screens at any given moment, just to avoid having to think too much about what’s going on out there.

We are, collectively, tired. There’s a real temptation to just stop caring about…everything. I think the fiction of the moment is all about this fight, this question. Do we actually care? Or do we just look away and let it all happen? Do we give up because the problems are too big to solve? Or do we each do what we can do, in our own infinitesimally tiny corner of the multiverse?

Does nothing matter? Or does everything?

I have a co-worker who loves anime and manga. Once, several years ago, he was in the bookstore, perusing the manga, and a boy sidled up to him. The kid was practically vibrating, he was so excited to tell him about the best manga ever: Naruto. My co-worker was all-too-familiar with Naruto and explained that he was not interested. But the boy insisted. Repeatedly rebuffed, he refused to give up. He was certain that this series was great, if only the dumb adult would listen. He pointed to one of the spines, some ten or twenty books into the series.

“Here,” he said. “See where the covers change color? That’s where it gets good.”

My co-worker, exasperated, threw up his hands and said, “I’m not going to read twenty books just to get to the good part!“

In the traditional story breakdown, the ending is one of the three parts of the story. It comes after the beginning and the middle. Or does it?

Today more than ever, media is business as well as art. And it is competitive. All the big gatekeepers are in competition not just with each other, but with all the little indie artists out there, from self-published e-books to rappers on SoundCloud to short films on YouTube.

Big media companies love a sure thing, or as close to one as they can get. Conveniently, after decades of mergers and acquisitions they also have warehouses full of old IPs and characters from all their previous successes. They are happy to use and re-use it, playing on nostalgia or even just vague familiarity. And even with brand new IP, they love to milk their stories and characters until they’re dry, desiccated husks.

More Star Wars, more Marvel, more Game of Thrones and Stranger Things and Lord of the Rings!

These modern mega-media empires are incentivized to make everything as episodic and ongoing as possible. Endings are bad for business. They want to sell more tickets, more monthly subscriptions, more merch. They want a multi-generational fan base. In short, they want the story to go on forever.

But stories aren’t meant to go on forever. They’re meant to end.

What drives a good story forward? What gets us excited and makes us eager to find out what will happen next? Well, Lincoln Michael would say that there are many different engines that can power a story.

Often the engine is about characters and their goals. They’re seeking something. Sometimes it’s mystery and discovery: something we want to find out. Machael suggests other options, like form, language and theme. However, all of these engines have some similarities. As we dig into them and begin to understand them, they get used up. The patience of the audience is a finite resource. Familiarity breeds contempt.

A character with a goal drives the story forward. They run into obstacles, they have successes and setbacks, and we root for them. But eventually, they have to make progress, whether that be success or failure. Eventually, they need to achieve their goal or have it slip out of their reach, or we get bored. Likewise, a mystery can only remain mysterious for so long. The clues have to lead somewhere. The red herrings have to be revealed eventually, or we’re left in a stew of uncertainty and frustration. The detective has to find the killer.

There are ways, of course, of stretching out that resolution. Perhaps the character fulfils their goal, only to discover a newer, bigger goal. Perhaps the original villain turns out to be just another henchman of the real villain.

These kind of tricks can only take you so far. The engine of the story eventually runs out of gas. You might be able to refill it once or twice by escalating into some exciting new territory, but if you go too long without a satisfying resolution, it all starts to fall apart.

Episodic stories might seem like the escape hatch. After all, the police procedural catches the killer at the end of the episode, and next time there will be a new case, right? But it doesn’t really solve the problem at all.

Episodic stories have two options: they can carry baggage from episode to episode, or they can wipe the slate clean every time. If they carry things forward, building larger arcs beyond episodes, then they wind up with the same problems of escalation as any other story. They need arcs, and they have to build toward endings. But if they wipe the slate clean, they run into an even bigger problem.

Episodic stories with no larger arc are cartoons. Often literally, but sometimes only figuratively. The world and the characters become static cardboard cut-outs. They can be played for laughs or drama for a while, but there are only so many times we can laugh at the same jokes or wonder “how will they get out of this one?” These are the zombie remains of real stories, still going through the motions, but utterly devoid of life.

No. For all my complaining, I’ve watched some of those shows. I’m actively reading several stories with no ending in sight. That’s fine. We can still get joy out of those things. Hell, Hollywood is banking on it.

It’s really just a missed opportunity. A good ending elevates the beginning and middle. A bad ending can ruin a good beginning and middle (which is why we collectively get so incredibly mad when the ending is bad). A story with no ending at all? We’ll never know if it could be great. It’ll just fade away slowly.

All of my favorite stories have endings. So really, this is just a plea for you to cater to my tastes.

Give your stories endings. Give them the opportunity for greatness.

I don’t typically talk much about my personal life on this blog. The blog is about writing, and I want to keep it that way, and not digress into the kind of parasocial voyeurism that pervades so much internet and television these days. However, I did want to drop a quick personal note today.

I’ve been absent from the blog and my other usual online haunts over the past week or so. Mere days into the busy start of the school year with three school-aged children, we had COVID make its way through the family. We’re all vaccinated, but I was still pretty effectively sidelined for a couple days, and the kids had to stay home from school.

I’m now on the other side of it, feeling fairly functional—only occasionally short of energy and a bit more easily winded. Everyone else is recovered or mostly-recovered. I’m thankful that we all had relatively mild and short-lived symptoms. I probably had the worst of it, and I really have nothing to complain about when considering what some people have gone through with this illness.

After what felt like an interminably hot and humid August, this weekend I got to enjoy air that feels cool enough to qualify as autumn weather. I went for a walk in the woods with the kids. I sat in the back yard with the monumental 865-page Ambergris omnibus hardcover. The cicadas are in high form, buzzing their raucous farewells to summer.

The parkway near our house was populated by only the most determined joggers and bikers in the mid-day swelter of a week ago, but in the cooler weather it now seems to have spontaneously germinated clusters of people like mushrooms: adults with their dogs and their children in strollers.

This week I feel like I’ve been given the opportunity to slow down; to watch and listen and “be present” (as trite as that phrase sometimes feels these days); to experience a series of peaceful moments, like little Norman Rockwell paintings. Maybe it’s a touch of altered consciousness, thanks to cold medications and COVID brain fog. Whatever it is, it feels like a nice break.

I’ll be back to the usual blogging soon. Back to Razor Mountain and the writing stuff. I’m already itching for it. I guess I’ve become a bit of an addict over these past couple years.

I recently reviewed a book by Lemony Snicket called Poison for Breakfast. It’s a delightful little book that has much to do with writing and stories, and as such, Snicket manages to sneak in a little helpful writing advice for authors.

Here are Lemony Snicket’s three rules for writing a book:

It is said that there are three rules for writing a book. The first rule is to regularly add the element of surprise, and I have never found this to be a difficult rule to follow, because life has so many surprises that the only real surprise in life is when nothing surprising happens.

The second rule is to leave out certain things in the story. This rule is trickier to learn than the first, because while life is full of surprises, you can’t leave any part of life out. Everything that happens to you happens to you. Often boring, sometimes exhausting, and occasionally thrilling, every moment of life is unskippable. In a book, however, you can skip past any part you do not like, which is why all decent authors try not to have any of these parts in the books they write. But few authors manage it. Nearly every book has at least one part that sits on the page like a wet sock on the ground, with the reader stopping to look at it thinking What is this doing here?

Nobody knows what the third rule is.

And as a bonus, advice for writing a good sentence:

Almost always, shortening a sentence improves it. A nice short sentence feels like something has been left out, which helps give it the element of surprise.

Genuinely helpful writing advice, or confusing nonsense from a silly book about bewilderment? I’ll leave it for you to decide.

In the halcyon days of the mid-2000s, the exploding popularity of alternate reality games got a lot of Silicon Valley types excited about the power of games to motivate people. For a few years, investors were happy to throw money at any product that included the word “gamification.” A handful of useful or interesting products came out of that wave of gamification, like StackOverflow and the StackExchange network it spawned, but a lot of attempts at gamification just slapped points and badges on drudge work in the vain hope that people would suddenly love it. Those products all sucked, and mostly disappeared.

Still, the idea of gamification isn’t completely useless (probably). I’ve browsed the ARG scene in years past, strictly as a casual observer, not a front-line puzzle-solver. In the best cases, it’s an interesting vehicle for storytelling, and it can be pretty amazing how effective a small group of people are at solving a problem when they’re all having a good time and feel like a community. I read Jane McGonigal’s book, Reality is Broken, and while I didn’t exactly come away believing that gamification can fix all the world’s ills, I think it can sometimes be useful as a way to self-motivate.

So anyway, that’s why I sometimes think about treating real-life writing as a role-playing game.

Do you want to play Writing: The RPG™? You can! All you have to do is follow these easy steps that I’m making up on the spot. Get yourself a couple pieces of paper.

Your character levels up by gaining experience points. You start at level 1. To gain a level, you need to get as many experience points as (your next level) x 2. So you need 4 XP to level up to level 2, and 6 XP to level up to level 3.

To gain experience, you have to do stuff related to your classes.

Writing: The RPG™ supports unlimited multi-classing. You can add as many new classes or sub-classes to your character as you want to. To add a class or sub-class, you have to complete a related task. You can’t get the Editor class until you’ve edited something. (Like really edited. Edit a chapter of your novel or something. Just fixing a couple sentences doesn’t count. This is serious business.) If you want the Blogger class, you need to post a blog post, and if you want to subclass into Fashion Blogger, that blog post better be about fashion, dangit.

There is none. It’s just a silly game. But maybe it’s a silly game that could actually motivate you to do something you kind of already wanted to do anyway? That’s what gamification is supposed to be good for, after all.

What do you think? Can we come up with more rules? I hearby release Writing: The RPG under a Creative Commons public domain license (no doubt giving up my chance to make millions from a half-assed afternoon blog post). Leave a comment with your additional rules, modifications, complaints, or erotic fanfic mash-ups down below.