We’re doubling up two months again! Why? Because I didn’t read much in September, and by golly, I’m all about providing maximum quality to my readership.

Where possible, I’ve included Bookshop affiliate links instead of Amazon. If any of these books pique your interest, please use those links. I’ll get a small commission, and you’ll support real book stores instead of private islands for billionaires.

Dune, the Graphic Novel — Vol. 1, 2, 3

Adapted by Brian Herbert and Kevin J. Anderson

Illustrated by Raul Allen and Patricia Martin

Dune is one of those perpetually evergreen sci-fi books that has somehow managed to maintain relevancy for more than half a century. This graphic novel adaptation of the book comes on the heels of the big budget Denis Villeneuve movies (despite the fact that those movies also have graphic novel adaptations).

I’ll admit that I had uncertain expectations for these books. Dune is fairly dense, as evidenced by its longevity and the very different adaptations that have been made over the years. These three volumes cover the plot of the original book, but there was no way to make it work in comic form without significant trimming. Even beyond that, Dune is a book that is often dialogue-sparse and heavy on characters’ internal thoughts, and this is a challenge that any visual adaptation needs to overcome.

The framing in the first book mostly stays out of the way. It’s nice and clear, but avoids any interesting or dangerous choices. There are a few multi-panel zooms and pans; a variety of big and small, wide and narrow panels; but almost no verticality in a medium where pages are taller than they are wide, and not a single curved line. It’s all rectangles, all the time.

However, the second and third books expand into a much wider variety of framing techniques. There are several pages with interesting nested circular frames, and a little bit of blending with nebulous or absent frames. It’s not quite the insane level of frame shenanigans you’ll see in something like Sandman: Overture, but it’s still praise-worthy.

The art is a little inconsistent, but never bad. There are a few faces and figures that come across as stilted or flat. It improves steadily in the second and third volumes. If I was disappointed, it was only because the whole package didn’t quite live up to the potential shown in some of the best, gorgeous full-page spreads. Hoo-boy, that full page sandworm reveal shot is fantastic. Color is used to great effect, with the characters and elements of House Atreides shaded blue, in contrast to the reds and pinks of House Harkonnen and the planet of Arrakis.

It tells the story competently, but I would have really loved to see more of that classic sci-fi strangeness. For all of the aspects of Dune that feel tropey in modern sci-fi (cough-cough-desert-planet-cough), it is a book where the people, places and cultures feel genuinely foreign and weird. The best aspect of the much-lampooned 1984 David Lynch movie adaptation was that it leaned into that weirdness. Even the Hollywood-friendly Villeneuve movies capture some of that magic with the Sardaukar throat-singing, insectoid spaceships, and psychopathic man-baby Harkonnen aesthetic. Here, the clothes, the technology, the landscapes all look a little too normal.

The story did, as I expected, suffer in some ways due to the inherent trimming that had to happen to fit into the graphic novel form factor. There is no room for expanded dialogue or exposition. The writers do take advantage of the ability to make characters thoughts visible to the reader. Ultimately, this is a slightly abridged version of the story, but there are only a couple of places where the development feels rushed as a result. The story isn’t broken, but it’s occasionally bent and loses some nuance.

My daughter (who didn’t really pay attention when I was reading the original book with my son) decided to read these books as soon as I was done with them. While I thought they might serve as a lighter, easier introduction to Dune, especially for a younger reader, her opinion was that it was still pretty confusing.

The Subtle Knife

By Philip Pullman

This is the second book in the Dark Materials trilogy, which I’m working through for bedtime reading with my children.

The Subtle Knife is a very different book from The Golden Compass. The first book takes place entirely in a secondary world, and feels like a traditional fantasy novel. It follows Lyra Belacqua, who is the classic precocious child/chosen one archetype. This second book takes Lyra into our world and another fantasy world, and introduces a second viewpoint character named Will Parry.

Will’s story is darker and hits a little closer to home, since he hails from the “real” world, and his problems, while extreme, are more relatable. I was curious to see how his story connects to Lyra’s. It’s clear that there are parallels between the two worlds, so I assumed the two characters are entangled in ways they don’t understand.

Pullman doesn’t lock us into a strict POV—the book jumps between Will and Lyra—but it does feel like Will is heavily favored, and certainly seems to make more meaningful choices. Lyra often seems to be pulled along as a sidekick, and this is a significant demotion of her character after the first book. I wonder if this pairing would have felt more natural if Pullman had included parts of Will’s story in the first book, even if Will and Lyra didn’t cross paths until the second.

The book ends with a strange series of events. An important character dies for a reason that was only lightly hinted at once. Another major character dies because he forgot that he had a “get out of jail free” card until it was too late. The villains, after being completely stymied for the entire book, are suddenly pretty effective. And it looks like book three is going to be even moreso Will’s story, at least to begin with.

The feeling I had when reading The Golden Compass was that this is a serious kids’ fantasy series that doesn’t quite succeed at achieving the plot, deep characterization, and world-building that other YA fantasy has achieved in the last couple decades. That feeling is not going away here.

I do still believe that Pullman has some genuine weirdness in his setting and plot that deviates unusually far from the classic Tolkien fantasy formulas, and I really hope that it will blow up in book three.

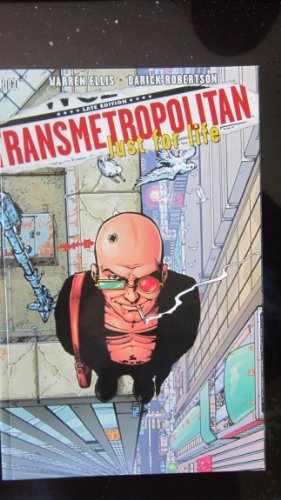

The New Age of Apocalypse

By Larry Hama, Akira Yoshida, Tony Bedard

As I mentioned in my August recap, I discovered a lost box of superhero comics when I moved to my new house. This month, I re-read the “new” Age of Apocalypse.

The original Age of Apocalypse was a big cross-book event that ran for four or five months across all of the X-Men books in the mid ’90s. It’s my favorite thing in superhero comics, although that is probably a function of my age when it hit, the state of Marvel at that time, and a good dose of classic nostalgia. I also don’t really read superhero comics anymore, so there’s really no opportunity for anything to usurp it.

The New Age of Apocalypse is the trade paperback collection of a limited-run series that released for the 10-year anniversary of the original event and picks up the story in the same alternate universe where the originals left off.

The book is drawn in the same heavy-lined, anime-inspired style of the Ultimate X-Men books I reviewed in the August read report. This style is clean and easy to read, and the artists are certainly skilled and make it work, but something about it just rubs me the wrong way. It’s a little too cartoony.

The story follow’s Magnetos X-Men as they try to pick up the pieces in the wake of Apocalypse’s collapsed North American empire. There is a mystery element, with Mr. Sinister playing the villain, but the resolution of that mystery ends up being…kind of dumb. There is a soap opera quality of over-the-top character motivations and emotions, and some of the characters change their minds seemingly at the drop of a hat. If I’m being charitable, I’d say that the writers tried to cram too much plot into relatively few issues, and this explains the abruptness of the action and mood swings of the characters.

Much like Ultimate X-Men, the New AoA feels like a classic comic book story with classic comic book failings. It’s a little more disappointing to me, but that’s only because I have such a fondness for the original AoA.

On that note, my box of old comics does include almost the entire run of the original Age of Apocalypse. I’m a little afraid to read those issues again, lest I discover that it’s not quite as good as my faded and nostalgic memory would claim. But I might do it anyway.

The Witcher: The Tower of Swallows

By Andrzej Sapkowski

Dear God, I did it! After several months of promising that I would get back to it, I finally finished this book.

The Tower of Swallows is the penultimate volume in the main five-book Witcher series, and it suffers a bit of the classic long fantasy series syndrome. All of the characters are wandering across the land, spending a long time trying to get somewhere for something to happen.

Our three main characters, Ciri, Geralt, and Yennefer, are all split up for this entire book, and I suspect this is a lot of what slows it down. They each have their own cast of secondary characters in orbit, and while a lot is happening, it still ends up feeling like all the pieces are being lined up just right for everything exciting to happen in the final volume.

That said, it’s still a good book in a great series. The setting, heavily inspired by Polish mythology, continues to shine. The world feels alive with complexity and depth, and even the characters with supernatural powers are often at the mercy of bigger cultural and political forces.

I’m beginning to feel that Sapkowski’s literary calling card is his ability to build a narrative through a dozen little frame stories. The book is a mix of flashbacks and retellings of events from different perspectives: a bard’s memoirs, a late night story next to the hearth, or the testimony of a soldier on trial for treason. It’s to the author’s credit that all of these blend together into a cohesive quilt of smaller stories.

With any luck, I’ll finish the final volume before the end of the year. I’ve really enjoyed my time with the Witcher and his cohorts, and I’m hopeful that Sapkowski will answer the remaining questions, finish off the biggest villains, and bring it all to a satisfying conclusion.