March has begun with an unseasonably warm weekend. Here in Minnesota, where we’re used to rough winters, it barely feels like we had any winter at all. Let’s jump back to February for my monthly report on what I’ve been reading.

To stay on theme, I’m trying to read more short stories this year. I end up reading quite a few while researching markets, but I’ve also got a stack of anthologies on my bookshelf that I’ll be reading as the year goes on.

I’m getting close to wrapping up the read-through of Harry Potter with my kids, and I finally returned to The Witcher series after an unplanned hiatus.

Where possible, I’ve included Bookshop.org affiliate links instead of Amazon. If any of these book pique your interest, please use those links. I’ll get a small commission, and you’ll support real book stores instead of gig economy worker abuse.

Time Shift: Tales of Time

Edited by Eric Fomley

For my February short stories, I picked Time Shift, an anthology of time travel flash fiction I picked up as a backer reward from The Martian Magazine.

Anthologies like this are awesome when you only have five or ten minutes to read. This one is even nicely pocket-sized. However, I’m reminded why I don’t like narrow themes like this. While any of these stories, individually, is good, thirty-eight stories about time travel, all in a row, started to feel repetitive.

If you like time travel and flash fiction, this is certainly the anthology for you. But if you’re like me, you might want to only consume them a few at a time.

The Witcher: The Time of Contempt

By Andrzej Sapkowski

I never intended to take a break from The Witcher series, but I got distracted by this and that, and suddenly a few months had gone by. The Witcher books consist of a five-book series, along with three anthologies of short stories that interconnect with the larger story. Time of Contempt is the fourth Witcher book, and the second book in the main series.

The setting for the story is the Northern Kingdoms, about a dozen countries of various sizes in a vaguely Nordic, medieval, semi-feudal fantasy world. A few years have passed since the attempted invasion of the huge southern Nilfgaardian Empire was barely stopped by an alliance of kingdoms and sorcerers in a decisive battle.

The Witcher, Geralt, had had his run-ins with royals in the past, but he’s made a point of staying out of politics. Now, however, he finds himself entangled by his ties to his adopted daughter, Cintran princess Ciri, and his sorceress partner Yennifer. War is brewing again between the Northern Kingdoms and Nilfgaard, but back-stabbing politics between kingdoms and factions of sorcerers make it look increasingly unlikely that the North will be able to unify again against their stronger adversary.

Ciri, despite her kingdom lying in ruins, is sought by royals and spies on both sides for her ability to legitimize claims over disputed lands near the center of the conflict. Some would kill her, while others would use her as a figurehead for political marriage. Even worse, she is believed by sorcerers and others to be the prophesied Child of Elder Blood, who may be destined to set off and/or finish a conflict of apocalyptic proportions.

Sapkowski does a great job combining the often humble difficulties of these powerful—but ultimately fallible and mortal—main characters, with the politics and machinations of classic high fantasy. All of the big movements of the world are revealed through small interactions. The widespread preparations for war are shown by following a royal messenger as he delivers secret messages, or the changes in market prices noted by a banker who sees the rich hedging their bets and fleeing in droves.

Geralt is the reluctant hero who could theoretically just walk away from all of this, but the people he loves cannot, so he gets drawn in through his efforts to protect them. He’s a likable character because he’s smart and moral, but he’s perpetually fighting a defensive fight to shield his family from forces he doesn’t entirely understand. The surface-level causes and effects of the war make sense, but it’s clear that there are deeper drivers of world events that haven’t yet been revealed: the Emperor of Nilfgaard and the Sorcerer Vigelfortz are both after Ciri because of something to do with the prophecy, but we don’t know why.

The languages and cultures of the world are, for my money, on par with the greats of the fantasy genre. The world is more gritty and grounded than the squeaky-clean high fantasy of Lord of the Rings, and the Polish influences make it feel distinct from the glut of generic Western European D&D knock-offs. The Elder Speech used by non-humans and sorcerers feels like a real language, and though few words are directly translated, it is consistent enough that phrases and patterns become familiar and recognizable.

Having recently read Palaniuk’s book on writing, I noticed some similarities in Sapkowski’s style. Palaniuk advocates writing each chapter of a book as a short story that can effectively stand alone. The early Witcher books are short stories that contribute to a larger narrative. The series books are more focused, but most sections are still nicely self-contained, and there are many smaller pieces within the narrative that could stand alone, without the context of the series.

The Time of Contempt ends with the three main characters separated, each of them in a bad place. However, they are survivors, and the question is how they will be able to get back together and solve the problems that plague them.

If it isn’t obvious, I’m delighted to be back in this series. It’s a joy to read, and I plan to plow through the rest of the books in the near future.

Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince

By J. K. Rowling

Half-Blood Prince might be the most interesting Harry Potter book. In a series that relies on patterns that repeat in each book, this is the book where most of the patterns get broken.

The Harry Potter books usually slavishly follow Harry’s perspective. Half-Blood Prince, however, opens with two chapters where the namesake character is conspicuously absent. The first is a meeting between the newly elected wizard Minister of Magic and the “muggle” Prime Minister, showing just how much the war between wizards is bleeding out from their usually secret world. The second is a meeting between the bad guys where a promise is made that will be fulfilled at the end of the book.

This collapse of familiar structures mirrors the plot: the order of the wizard world, and the world as Harry Potter understands it, is falling apart. Despite this, it might be the most well-plotted book in the series.

The language in this book is also different. This is partly a continuation of the trend away from the childishness of the first few books, as the language grew alongside the audience. It’s also clear that some of this came with Rowling gaining experience. I’m sure she had a stellar editing team at this point as well. However, I suspect that the language is more cinematic, more vividly descriptive, partly because Rowling had the opportunity to see the first couple books adapted as movies by the time the series was wrapping up.

The ending of this book is, of course, the big twist that has become something of a meme by now. But that’s because it’s a pretty good twist. It’s hard to imagine a bigger, more unexpected plot point for the series, short of one of the three main characters dying. This ending really is the ultimate way to signal that the story is now off the map. The final book will do without the patterns and conventions of the previous six, and will tread into the darkest territory of the series.

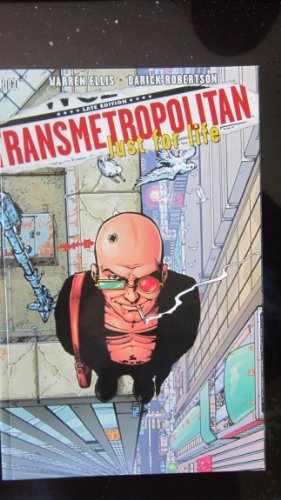

Die

By Kieron Gillen, Illustrated by Stephanie Hans

I fell backward into this series, reading the TTRPG rulebook based on the comic before I got the book itself. My understanding is that they were created in tandem though, so it seems appropriate.

The book itself is a beautiful, monstrously thick hardback with an understated black cover. The slightly oversized comics form factor feels oddly tall and skinny for a book with this much heft. The art is full color, and the style is dreamlike. Almost every panel is either crowded with shadows or blown-out with background light.

The first two chapters describe the backstory: a group of misfit teens play a magical RPG that sucks them into the fantasy world of the game. They don’t return until two years later, missing one person and one arm, and considerably worse for wear. They never tell anyone what happened to them.

Twenty years pass, and they meet up again, brought together by the mysterious return of the magical dice that transported them, and memories of the player they left behind. Most of their lives aren’t going well. They still carry the traumas of their past. Once again, they’re sucked into the fantasy world of Die.

Like so many of the stories I’m drawn to, Die is a metafiction, obsessed with the structures and dynamics of stories. Where Sandman is a contemplation of dreams and myths, and The Unwritten is a study in fantasy tropes, Die is an analysis of story and conflict in tabletop RPGs, and the interplay between players, player-characters, and the game. In fact, the back of the book is taken up with a number of essays on TTRPGs written concurrently with the story itself.

Unfortunately, I feel like Die is a little too eager to define itself in shorthand references to greater works. It bludgeons the reader with big nods to Tolkein, Wells and Lovecraft, but they are shallow references, and not enough new and interesting is built on top of them. Die is constantly saying things like

The Fair are…”What if William Gibson designed elves.”

…or…

Glass Town is Rivendell meets Casablanca, Oz in No Man’s Land.

Eventually, I found myself desperate for something in the world that wasn’t described in terms of something else. Unfortunately, the gods of Die and the Fallen half-zombies are the most unique aspects of the setting, but they’re only rarely touched upon. I couldn’t help feeling that Die is a little too clever, and a little too eager to show you how clever it is. There is a certain cynicism to a story that hides behind its influences. By not exposing its heart, the story and the author don’t leave themselves open to praise or criticism in their own right.

Die is driven by a simple idea: the characters are trapped in this fictional world, and the only way they can go home is if they all agree to it. The challenge is that they do not get along, so getting everyone to agree is no simple task. It can’t be done through force, only through negotiation.

While that’s a fun concept, I felt like the motivations of the characters were too mercurial. Their disagreements and fights felt too arbitrary, too inorganic. It’s the soap opera problem, where the characters whims shift in service to every twist and turn in the plot.

In retrospect, I see that a lot of my review here is negative, and that is probably unfair. Die ultimately didn’t quite land for me, but it does do a lot of things well. The art is beautiful, and it presents a huge number of interesting ideas. And while many of them work on a granular level, they don’t quite mesh into a satisfying whole.

I’m not the most die-hard fan of TTRPGs, but I’ve played a decent amount. Over the years, I’ve come to realize and accept that the story in a TTRPG campaign will never conform to the shape of a well-crafted novel or movie. As a GM, trying to make that kind of story is a mistake. It can’t work when there are four or more people all driving it together. There will be tangents. It will meander. And that’s okay. It’s a different sort of experience than a novel or movie. Despite the incredible popularity of TTRPG “actual play” podcasts and videos in recent years, I firmly believe these stories are more enjoyable as a contributor than they are as an external viewer.

Strangely, I feel the same way about Die. I can feel a great story in there for someone, I just wasn’t able to experience it myself.

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Vol. 1

By Alan Moore, Illustrated by Kevin O’Neill

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen was originally published in 1999. Ironically perhaps, for a series that cribs from the earliest science fiction, it feels older than that. I suspect that feeling is due to the outsized influence that League has had on indie comics. We see echoes of it in many things that came after, so when we return to the original, it seems a little less unique and strange than it did at first. But it still holds up pretty well.

If Die is a story that rubs me the wrong way with its blatant references to other stories, League is the polar opposite. Practically every single page is jammed to the gills with references to turn of the 20th century proto-science-fiction. However, there are no winks and no nods. The story doesn’t feel the need to draw attention to the references.

In the first few pages, our scarf-clad main character, Mina Harker (né Murray) meets with her employer, Campion Bond, who works for a mysterious M. Then she’s off to retrieve a second main character, the opium-addled Alan Quatermain, taking the taciturn Mr. Nemo’s submersible. The League is rounded out with the help of Mssr. Dupin in acquiring the two-faced Dr. Jekyl, and they locate a certain invisible man at the estate of Rosa Cootes.

The story is so stuffed with familiar names that it’s easy to latch on to Jekyl or Nemo or the invisible man and not worry about the rest. But an avid reader can search out every name and turn up another interesting lost corner of old pulp literature. League draws upon an absurd number of stories and mashes them together with reckless abandon. The result is something pulpy and silly and occasionally self-serious in much the same ways as the stories that it cribs from.

The story fully embraces the casual racism, sexism, self-righteous colonialism, and all the other -isms endemic to the British Empire as it approached the 20th century. This could easily come across as crass, but it manages to feel accurate to that world and time period. And as the main characters tend to be on the receiving end more often than not, it doesn’t feel as though these ideas or behaviors are condoned.

That’s not to say that the protagonists are good people all of the time. Or even most of the time. They don’t get along with each other, let alone the rest of the world around them.

The art is a style that I’m not sure I’ve seen elsewhere. It’s detailed and scribbly in equal measure, with impossible, caricature proportions that combine realistic and cartoon aesthetics.

At the end of the six issue series is a lightly-illustrated bonus story called “Allan and the Sundered Devil.” This adds a little more color to Quatermain’s character and acts as a mini-prequel to the main story. It leans into the pulp fiction premise of League even more than the comic, and the prose is so purple that I found it a little much to read.

This is the only volume that I’ve read previously, but the pile of comics I received at Christmas included three more volumes of League. I’ll be reading those in the coming months and seeing how they hold up compared to the first. This one, at least, I would consider a must-read for any fan of non-superhero comics.

What I’m Reading In March

The final book of Harry Potter, the continuation of The Witcher and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. For short stories, I’ve got some light reading lined up in The Complete Works of Ernest Hemingway.