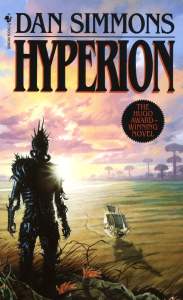

Book | E-book (affiliate links)

Reading the four-part Ender’s saga left me feeling skeptical of big, philosophical, late-80s sci-fi books. Now I’m going back to that well with Hyperion.

I’ll be honest, Hyperion feels clever and stylish after Children of the Mind. Then again, Ender’s Game was the first and best book in the series. Hyperion is also the first book in a four-book series. So maybe I’m setting myself up for heartbreak all over again.

Canterbury Tales, in Space!

Hyperion opens with a frame story. A man we know only as the Consul is given instructions to go to the planet of Hyperion along with six others, on a mysterious pilgrimage. He goes, and meets his compatriots:

- Het Masteen, captain of the spaceship that will transport them, which just so happens to be a giant tree.

- Father Lenar Hoyt, a Catholic priest in a galaxy where Catholicism is nearly extinct

- Colonel Fedmahn Kassad, a soldier of the galaxy-spanning Hegemony’s military

- Martin Silenus, a centuries-old poet who has journeyed between stars and across time via relativistic space travel

- Sol Weintraub, a scholar, who brings his baby daughter Rachel

- Brawne Lamia, a hard-boiled private detective

When the pilgrims arrive at Hyperion and introductions are made, they come to an agreement: they will each tell the story of why they came as they make the long journey from the spaceport to their final destination, the Time Tombs. There, they expect to find the Shrike, a mythic creature made entirely of razor-sharp blades. Supposedly, he will choose one of them to grant a boon, and the others will be sacrificed.

As the journey gets underway, each pilgrim tells their story in turn. Between the stories, they travel across the planet toward their destination. It’s a bad time to return to Hyperion. The planet is poised to be the first front in the largest war humanity has ever seen, between the Hegemony and the long-exiled Ousters, who live strange lives in their deep-space ships. The Time Tombs—in what cannot be coincidence—appear to be opening, and nobody knows what will come out.

A Slowly Woven Tapestry

The structure of the book allows Simmons to expand the scope of ideas slowly. The unexplained and confusing in one story is addressed and answered in another. It allows the reader to assemble these small pieces into a detailed and rich setting.

Through the pilgrims’ stories, we begin to understand the galaxy they inhabit and the ways their paths have crossed Hyperion and the Shrike to bring them to the current moment. From Silenus we learn about Old Earth and the Big Mistake, a man-made black hole that slowly (and then quickly) devoured the planet, forcing the Hegira to many worlds. From Father Hoyt and Saul, we learn about Hyperion, it’s inhabitants, and the Time Tombs. From Kassad and the Consul, we learn about the armies of the Hegemony; the many rebellions quashed and small wars fought by a supposedly peaceful and democratic government. From Brawne, we come to understand the vast web of farcaster portals that allow instantaneous travel between Hegemony worlds, and the mysterious society of AIs who control them and remain apart from humanity while ostensibly guiding and helping them.

The book paints rich portraits of a handful of specific worlds. Dan Simmons manages to make almost every setting in the book genuinely strange and interesting. A planet wracked with storms, a sea of grass navigated by gyroscopic sailing ship, a 1.3g planet where the people live in vast arcology-like “hives,” a bus-sized cable-car over snowy mountains, an ocean world where people live on island-sized migratory creatures, and a vast capital city where the rich live in houses where every room is a portal to a different planet.

This feels like a universe with a history, a big universe populated by billions of people across dozens of worlds, and all the diversity that represents. It’s full of beauty and weirdness. And yet, the same human sins and weaknesses are still there, still causing problems.

Each pilgrim brings a different perspective to their story, which allows Dan Simmons to shift style and tone throughout. Kassad’s story is full of sex and violence, a pastiche of military sci-fi, while the Consul’s story is more of a historical documentary. Brawne’s story is a cyberpunk noir where the detective inevitably falls in love with her dangerous client. Sol’s story is that of a father desperately trying to save his sick child. These different styles help to keep the book constantly fresh, and each reveals new pieces in the puzzle of what’s really happening on Hyperion.

In the Ender Saga books, the relativistic effects of space travel were a promise that never really delivered. Nobody apart from the main characters traveled between worlds, and it seemed that nobody could even imagine that someone might live for hundreds of years by traveling between stars while time passes by.

In Hyperion, relativistic space travel is a part of life. The Web of Hegemony worlds are connected instantaneously via farcasters, but each world starts as a colony whose inhabitants took a many years to arrive, and even longer to build their first farcasters. Conflicts often arise between the original settlers, or indiginies, and the flood of tourists that inevitably come with joining the web.

Style Plus Substance

Ultimately, I think a lot of what I enjoy about Hyperion comes down to Dan Simmons’s writing style. It incorporates literary flashes and delightfully crafted language, while maintaining the workmanlike plotting and characterization that a mainstream science-fiction audience would expect…especially in the late 1980s.

For a thirty-five year old novel, Hyperion still feels fresh and interesting. It’s doing a lot, and doing most of it well. If there’s anything to critique, it’s that the book sets up some big mysteries and leaves the biggest ones unresolved. I believe the four books in the series are really a pair of duologies, so I expect to get most of the answers in the sequel, The Fall of Hyperion.