Well, we’re halfway through April, but I’m just getting around to my monthly reading recap. This month was mostly continuing series: The Witcher, League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, and finally finishing Harry Potter with my kids.

Where possible, I’ve included Bookshop affiliate links instead of Amazon. If any of these book pique your interest, please use those links. I’ll get a small commission, and you’ll support real book stores instead of mega-yachts for billionaires.

The Complete Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway

By Ernest Hemingway

Hemingway is often cited as the pinnacle of American short fiction, and I haven’t read any of his work since college. Perfect for my year of short stories. However, this particular collection is 650 pages, and I only managed about half of that in March, so I’ll be continuing in April.

If you’ve heard anything about Hemingway, it was probably that he’s known for his short, terse sentences. While those sentences are certainly present, he actually mixes up his sentence styles quite a bit. I feel like this description of him has been cargo-culted through undergrad English programs for decades. Possibly unpopular opinion: many of his best sentences are quite long.

While the majority of Hemingway stories are quite short and straightforward, the language is sometimes a little bit of a slog. We’re far enough removed from the times and places in these stories that it’s like visiting another land. The style and word choice is old fashioned enough that it’s sometimes like translating a different dialect. It’s not like parsing Shakespeare or anything, but I’m probably getting less out of it than a contemporary reader would.

None of these stories are particularly plot-heavy, and many are vignettes with scarcely any plot at all. They capture a feeling and a place and time, but I find myself wishing that more would happen.

If you’re a modern reader who is acclimated to fast-paced, plot-heavy stories, and you’re not interested in the historical value or the literary prose, I can’t really recommend reading all of the Complete Hemingway. However, I think anyone with an interest in short fiction should read at least a few of his more famous stories.

The Witcher: Baptism of Fire

By Andrezej Sapkowski

War is raging between the kingdoms of the north and Nilfgard. The Witcher is recovering from a near-fatal beating at the hands of the traitorous sorcerer, Vigilfortz. Ciri has become a bandit in Nilfgard, (though Nilfgard claims she is safe under the protection of the Emperor). Yennefer is gone, missing after the battle at the sorcerer’s conclave.

We appear to have reached the section of the fantasy series where the main characters are all split up and must fend for themselves. For Ciri, this means having to survive for the first time without the protection of Geralt or Yennefer, and falling in with a very bad crowd.

For Geralt, the Witcher, this means coming to grips with the possibility that he is not strong enough to protect the people he loves without some help. Despite himself, he collects a motly crew that includes his longtime bard friend, Dandelion; Regis, the old alchemist with a dark secret; Milva, the human archer allied with the non-human scoi’atel rebellion; and a caravan of kind-hearted dwarves scavenging and collecting refugees in the wake of battle.

Yennefer’s absence remains a mystery for most of the book, but she comes back into the story with a meeting of a new alliance of sorceresses from the north and Nilfgard. As usual, the wizards are always plotting ways to control the events of the world. Unfortunately, those plans still involve Ciri.

The strength of the Witcher books thus far is the way the story integrates the large-scale political machinations and battles with the personal connections between characters.

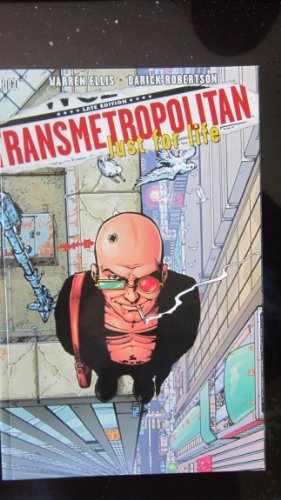

League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Vol. 2

Written by Alan Moore, Illustrated by Kevin O’Neal

We begin with John Carter and Gullivar Jones as leaders in a war of many races on mars. One alien race, holed up in a fortress, escapes in rockets headed for earth. Thus begins the Martian invasion of tripods, a la War of the Worlds.

The first volume of League was so short and introduced so many characters that there was limited opportunity to delve into each one. It worked, partly, because the source material was already familiar. In Volume 2, there is space for more characterization: romance, betrayal, and plenty of fractures and disagreements between the League’s members (as well as Bond, M, and the British government).

If Volume 1 was the origin story, Volume 2 feels like an abrupt finale. Two members of the League end up dead and the rest are estranged by the time the story is over.

The weakness of the series so far is that all these exciting characters have so little control of their own lives. The violent and self-centered Hyde and Griffin act on their own impulses, mostly to their detriment. Mina and Quatermain, and to some extent Nemo, are the “good kids” of the group, who actually follow orders, and are once again used to carry out actions they don’t understand or necessarily agree with. While the League plays a major role in the fight against the martians, I couldn’t shake the feeling that they were side characters in their own story.

Volume 2 concludes with a thirty-page illustrated travelogue that hints at several earlier iterations of the League, composed of literary characters from previous eras. It also hints at the future.

Like the Quatermain story at the end of the first volume, this was too tedious for me, and I ended up skimming by the end. There are tantalizing references to the previous Leagues and the adventures of Allan and Mina will have after the Martian invasion. But much like Calvino’s Invisible Cities, endless descriptions of fantastic places become dull when they have no characters or plot to anchor them.

League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: The Black Dossier

Written by Alan Moore, Illustrated by Kevin O’Neal

Set in the same alternate universe as the first two volumes, we’ve jumped to 1958. The totalitarian post-war Big Brother government has just fallen in England, and Mina Harker and Allan Quatermain are back after years abroad.

Black Dossier expects the reader to have slogged through the travelogue at the end of Volume 2, which contains a lot of mostly elided story. It explains where the pair have been all these years, why they are young-bodied and effectively immortal, who the heck this Orlando character is, and what exactly is up with the Blazing World.

Black Dossier is a very strange comic, a time-jumping multimedia extravaganza. It begins as an ordinary comic, as Mina and Quatermain trick a rather nasty version of James Bond into gaining them access to military intelligence records. They proceed to find the black dossier of information about all the different incarnations of the League, and make their escape.

Safely back at their boarding house lodgings, they begin to read the dossier. Then the narrative pauses to show the contents of the files.

The rest of the books shifts back and forth between Mina and Quatermain in ’58, fleeing military intelligence, and the dossier’s files, which range from lost Shakespearean folios to memoirs and maps, to borderline erotica/porn.

This book is incredibly horny. It makes some sense, with the pulp fiction roots that the series embraces wholeheartedly, but at a certain point it just comes across as a little juvenile, especially when some sections have no purpose in the story and exist just to be sexy.

The book ends with a 3D glasses chapter, and a play on the end of midsummer night’s dream — instead of comparing stories to dreams, it plays on the way science fiction has shaped the world over the years.

The League books have always been a mix of high-brow and pulpy. Unfortunately, the whole experience is pretty uneven. Some sections are dull and self-indulgent, feeling more like a collection of backstory notes than proper story, and it’s frustrating that you need to cross-reference everything to get a sense of exactly what’s going on.

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows

By J. K. Rowling

This final book of the series eschews the structures that have held fast through the previous books. Harry isn’t going to school. He’s on the run, searching for the immortal lich villain’s phylacteries horcruxes. The story alternates between a series of narrow escapes and heists.

The death of a secondary character at the end of the fourth book was fairly shocking compared to the surrounding material, but the tone is so much darker by this final book that major characters are dying every few chapters.

The biggest problem I have with this book is how much time the three protagonists spend wandering, with no idea what to do. They fight, separate, come back together. They argue and complain. The middle of the story gets bogged down and doesn’t seem to be going anywhere. It’s too bad, because the first third and last third of the book are packed with good action.

Right in the center of this soggy middle is a sequence where the main characters acquire an important macguffin without any effort on their part. This is all explained much later, but it still feels like a major success falling into their laps almost accidentally.

Finally, I have to complain at least a little bit about the amount of info-dumping that occurs in the last couple chapters of the book. The biggest info-dump comes through the pensieve, a magical device that allows Harry to view other people’s memories. This device is Rowling’s exposition machine in the latter half of the series, but it is exercised to such an extent in this book that we effectively get a whole chapter of wading through memories. I can’t help but feel that this was a bit of a cop-out, allowing Rowling an easy way to reveal all the important secrets of a major character right at the end, without any of the messy difficulties of figuring out how the characters could discover that information.

With all that said, and the occasional other complaints I’ve lodged in earlier Read Reports, the series holds up pretty well. It feels relatively unique in the way its voice changes so significantly from the beginning of the series to the end. It also creates a huge cast of interesting characters. So even if I may be irritated by the inconsistencies of the magic or the incredible dysfunctionality of wizard society and government, the story still gets me to care about what’s happening to Harry and his friends.

What I’m Reading in April

I’m going to be finishing off the League of Extraordinary Gentlemen with Volumes three and four. I’ll be reading the fourth novel in the Witcher Saga, Tower of Swallows. I’ll also be doing my best to finish The Complete Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway.