This is still a blog about writing fiction, but in this post I’m going to talk about video games and the way they can provide some unique narrative experiences that are difficult or impossible to achieve in other media.

Even if you’re not interested in games, it’s worth learning a bit about how narrative in games continues to expand what media is capable of. A good place to start might be interactive fiction, an art form that straddles the boundaries of prose and video games. Interactive fiction is where a lot of interesting experimentation is going on, but more and more “traditional” video games are incorporating narrative lessons that were originally explored by IF.

Gameplay and Narrative

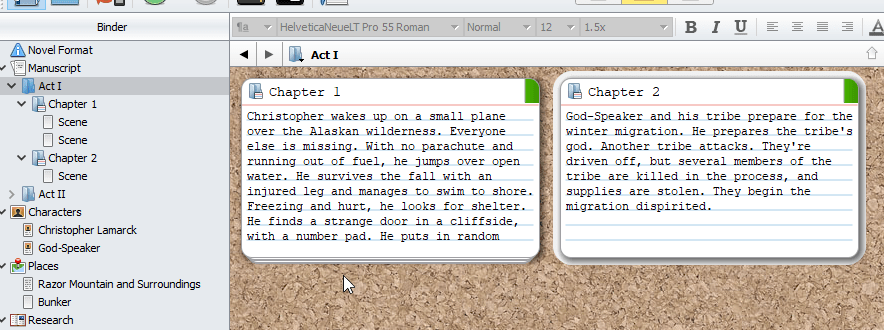

In many ways, the experiences in games can be tracked along two axes: gameplay and narrative.

I’ll define gameplay as systems to be solved or optimized. They are goal-based, whether implicitly or explicitly, and can be open-ended. Examples of gameplay include spinning and placing Tetris pieces or aiming and shooting opponents in a first-person shooter.

Narrative, on the other hand, is the “story” of the game. This may hew close to traditional story structures, as in film or fiction, but it can also branch, or even arise organically from the interaction of systems. Examples of narrative include branching dialogue choices in an RPG, characters talking in a cutscene, or distracting an enemy with a well-placed arrow in order to sneak past them.

I realize that there is a lot that could be argued within these definitions. I made them purposely broad, partly to illustrate how often we categorize narrative and story very narrowly.

Under these definitions, games may still range from no gameplay to all gameplay, and from no narrative to all narrative. However, the presence of one does not necessarily exclude the other — it’s not zero-sum, but it can require a deft hand to balance both.

Preconceptions

There is a certain set of gamers who think gameplay is the most important thing in a game. For this group, a game with little or no gameplay and lots of narrative doesn’t qualify as a game at all. These are the folks who coined the derisive term “walking simulator” for games that are entirely narrative, with little to no gameplay systems or challenges.

In opposition, we find the “games are art” crowd, who tend to be much more inclusive of walking simulators or visual novels, and appreciate narrative as much or more than gameplay. Many of the people in this camp will feel frustrated and excluded if a game has a lot of gameplay to wade through to get to the story, especially if it is difficult gameplay. If the player cares about the story, having that story blocked by gameplay that the player doesn’t care about can be irritating.

What Makes Game Narrative Special?

Games are a special narrative medium for two reasons:

- They’re experiential

- They’re participatory

In cinema, TV and books, the author will often try to create sympathy for a character. TV and movies have certain disadvantages here, because the visual media are always showing characters from the outside. Character narration is about as deep inside a viewpoint as they can get. Novels and stories, on the other hand, can use the first-person perspective to put the reader directly inside the character’s head. Even in third-person, they can reveal a character’s thoughts and emotions. The reader can more directly experience what the character experiences.

Games have a similar advantage, and go even further. In games, the player often controls or even inhabits a character. In this way, the player can experience what the character experiences. This is experientiality.

What a consumer of traditional fiction or visual media cannot do is take control of the story. Simple gameplay systems such as choosing where to walk at a given moment, or picking from several dialogue options, make the player an active participant in the story. Even if the choice is artificial and they are eventually funneled into a single location to progress, or the dialogue always ends with the same result, the feeling of participation is a powerful tool.

While other media can give the reader or viewer insight into a character’s thoughts and beliefs, games have a unique power to make the player feel unified with the character. The player becomes invested in the character’s actions as if it were the player making those actions, even when there really is no other option. Players often fall into first-person when talking about actions performed in the game. They say “I accidentally blew up the bokoblin camp,” not “Link accidentally blew up the bokoblin camp.”

Along with this fusion of player and character comes a strange feeling of player responsibility over the story. An unusual first person shooter called Spec Ops: the Line actively explores these concepts of narrative and player agency. The player has no real control over the story, moving from place to place and shooting everyone that moves. But when the characters participate in war crimes, the game asserts that the player did these terrible things. Because of the unification of player and character, it’s hard not to feel some amount of responsibility, even though the only other choice is to put the game down and walk away.

Simple experientiality can be as powerful as active participation and choice, but that power is often underestimated. In What Remains of Edith Finch, the player spends most of the game exploring the many ways that the members of the supposedly cursed Finch family died. It quickly becomes apparent that whenever you encounter a new character, they are destined by the narrative to die. It’s surprisingly crushing then, when you reach a point in the game where you discover that you are inhabiting the perspective of a small child, left alone for a moment in the tub. You know what will happen, and the very fact that you have no power to make a choice to change that outcome is gut-wrenching.

Bringing it Back to Fiction

Games can deploy experientiality and participation to create stories that would be impossible in other media. But is there anything in these concepts that we can bring back to our fiction writing?

I think there is, although it’s a challenge. We may have to dip our toes into the experimental end of the pool.

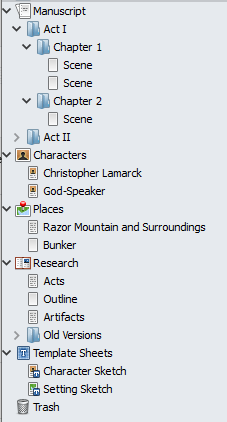

Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves is an experimental novel that contains a layered narrative. It presents itself as a book pieced together from disparate documents, collected by multiple authors, and based in turn on lost video footage. It carefully passes the story through this chain of custody, from Will Navidson’s videos, to the old man, Zampanò, to the narrator, Johnny Truant. Implied within this is that the reader is the latest custodian of this story, which has driven its previous owners to obsession and insanity.

The text itself is cryptic and formatted in a variety of strange ways, sometimes swirling around the page with swaths of whitespace, colors or boxes. It is riddled with footnotes (and footnotes to footnotes), “supplementary” materials, and copious references to other works, both real and fictional. In some places, the text is so disordered, the reader must choose the order to read it in. At a broader level, the reader must make connections between disparate pieces of text across the book to assemble the story.

Simply by reading the text, the reader becomes a sort of detective, trying to derive meaning from this carefully constructed mish-mash. The reader begins to feel what Johnny or Zampanò might have felt as they compiled scraps of text into the book, or scrawled bewildered footnotes late into the night.

House of Leaves is a challenging book to read, and was no doubt a challenging one to write, but it is clearly trying to pull off the same tricks that many games achieve: to make the reader feel that they are experiencing and even actively participating in the story.

Trade-offs and Opportunities

Different forms of media will always have trade-offs — things they do better than other media, and things they do worse. For games, experientiality and participation are powerful storytelling tools. Working in fiction, we will always struggle to leverage those tools as effectively as games can.

Still, there are lessons that can be learned from this style of narrative, and perhaps opportunities to allow the reader to experience the story and even feel like an active participant.