Games are uniquely positioned as the newest narrative art form, the baby of a family that contains novels, stories, movies and television. Narrative games are an even newer invention—after all, there is no story to speak of in Pong, Space Invaders or Pac Man, and even many modern games still treat any sort of narrative as an afterthought. We’re still feeling our way through the possibilities opened up by this young new media.

Last time I talked about narrative in games, I discussed the two techniques games use to immerse the audience in the story: experience and participation. Recently, I’ve been thinking about these concepts, their limitations, and how they work together.

Inhabitive Experience

The first thing I want to do is redefine the idea of experiential narrative that I introduced in the original post. This is the idea that games immerse the audience by allowing them to directly experience being in the story.

Other kinds of media can provide this to a lesser degree. Many modern stories use close perspectives, where the audience sees the world of the story filtered by the character they are close to. The most extreme close perspective is first-person limited, where the audience seems to float somewhere in the back of the main character’s head, or reads their telling of the story after the fact.

Interestingly, one of the least-frequently-used perspectives in modern media is second-person. While third-person dictates the story from outside the characters and first-person provides the internal view from within a character, second-person provides the odd perspective of having the story directly addressed at “you,” the audience. (90s kids will remember the Choose Your Own Adventure series.)

Many games make the player see through the eyes of a character, and this is typically referred to as a “first-person” in terms like FPS: first-person shooter. However, there’s an argument to be made that the experience games provide is actually second-person in nature.

In a game, the player can inhabit a character, in the same way that a person comfortable with driving a car acts as though the car were an extension of themselves. When someone talks with the character, they also talk directly to the player. When something happens to the character, it happens to the player.

This inhabitive experience is the core of what allows games to be emotionally impactful.

How to Inhabit a Character

Counter-intuitively, detailed characters are easier to inhabit than generic ones. The history of video game writing is littered with generic protagonists, created with the mistaken belief that an empty vessel makes it easier for the player to step into the game.

A generic character doesn’t give the audience any place to root themselves in the story. There are no attributes to embody, no desires or aspirations to connect with. The player is dropped out of the sky into a foreign world, but the character they inhabit should not be. That character is the audience’s gateway into the world, and when the character has connections in the world, the player can learn about the world through them.

Participation is Secondary

In addition to inhabitive experience, there is a second trick that games use to immerse the player in the story: participation. Instead of merely experiencing the story, the audience can actively participate in it.

Participation can vary quite a bit. While some games allow the player’s actions to influence the narrative, in many cases the plot points are set in stone. In other cases, the player might decide what order a series of events happens, even if all those events must happen to progress the narrative. This may sound meaningless, but when done well, this small amount of choice can provide the player with a sense of agency.

Even simple participation, like freely exploring a confined area, gives the player a certain sense of involvement. The truth is that participation in the story does not necessarily mean control over the story. The player can be complicit even if they’re not in charge.

It is also important to note that participation, by itself, is not enough to create a narrative experience. The player is a very active participant in a game of Tetris. Even more complex games like city-builders and real-time strategy give the player complete control over the game pieces, but that control has little bearing on the story, if a story is even present.

The Key Narrative Combo

Participation must be paired with an inhabitive experience to create an effective narrative. The game places the player into a character that they can empathize with, then gives the player some degree of control over that character. Now, when the character encounters a series of story events, the player inhabiting that character experiences the events personally, and feels responsibility for the choices they make on behalf of that character.

Unfortunately, simply having these elements in the correct configuration doesn’t automatically make for a compelling story. The setting, characters and other typical story elements still have to be well-crafted to draw in the audience. These are only the prerequisites.

I can look at any of my favorite narrative games and find exactly these elements: a detailed and interesting character, rooted in an interesting world and given problems to overcome. The player is then given control of that character. Beyond that, the story is still a playground for the writer to choose what story they want to tell.

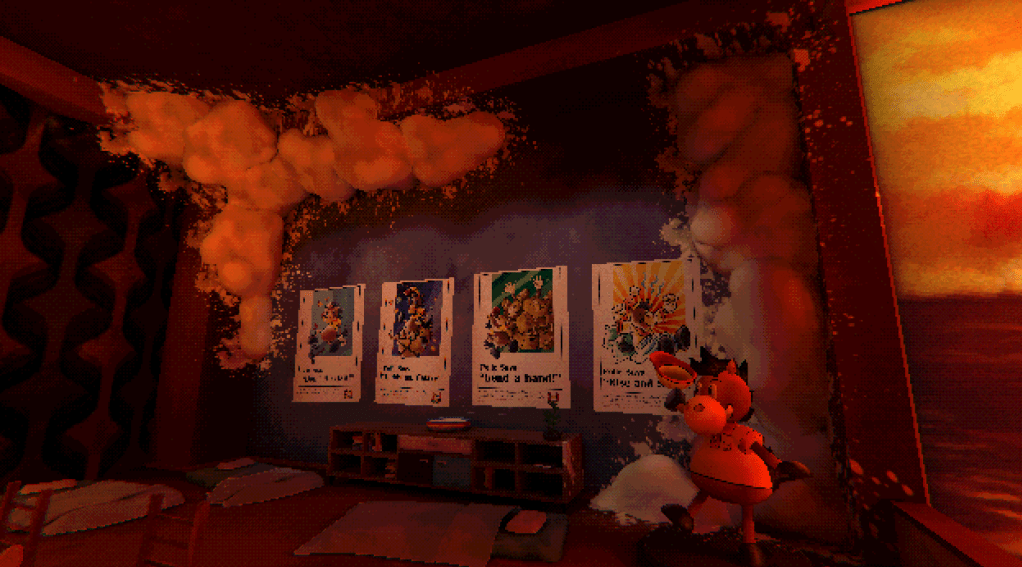

In Psychonauts, that’s a young misunderstood psychic boy trying to save the world and also fit in at summer camp. In Firewatch, it’s an emotionally vulnerable man spending a summer as a park ranger, trying to figure out how to mourn his dying, comatose wife.

Emergent Narrative is a False Promise

A popular idea when discussing deep narrative games is the promise of “emergent narrative.” Modern games are made up of many complex systems, and the argument in support of emergent narrative is that the player can interact with sufficiently complex systems to generate interesting stories that even the creators of the game couldn’t predict.

On a certain level, this is true. My family has certainly told each other stories about the ways an attack on a bokoblin camp can go surprisingly right (and terribly wrong) in Zelda: Breath of the Wild. These stories can involve an inaccurately thrown bomb knocking things around chaotically, or a well-aimed arrow miraculously saving the day.

Likewise, notoriously buggy games like the Elder Scrolls or Fallout series generate endless stories of unexpectedly levitating horses, launching enemies into orbit with a strangely-angled strike, or even stealing the entire contents of a shop after blinding the shopkeeper with a bucket placed over his head.

These make for fun anecdotes, but not for deep, impactful stories. They typically have an element of the comedically absurd or completely chaotic, and that is because the interactions of the player with multiple complex systems will naturally contain a large element of randomization.

Chaos and randomization can be fun, but they do not lend themselves to deep and affecting narrative. Narrative requires structure, and while authors and creators may argue endlessly about what structures work best, emergent narrative is inherently structureless.

We might argue that the job of the game writer is to anticipate or corral the player’s actions, aligning them with the game systems in such a way that a narrative naturally emerges. To me, this sounds like mixing oil and water. Players will always think of options that the creator didn’t anticipate. And if the creator effectively corrals the player into a pre-planned story, it often becomes apparent to players that they are being offered the illusion of choice. The narrative isn’t emerging. It’s being forced. This is something The Stanley Parable explored to great comedic effect.

That’s not to say that a carefully authored story is a bad thing in a game. In fact, I think it’s the only effective way to craft a good game narrative. Emergent narrative can be fun, but it will never result in the same quality of story that purposeful authorship can achieve, just as the proverbial thousand monkeys with typewriters will never produce Shakespeare.