There is a truism among authors that has been passed down for many years: “Money should always flow toward the writer.” In a world where many writers are desperate for recognition and the opportunity to be published and read, and where many unscrupulous people are happy to prey upon them, this is a good default attitude to have.

However, the publishing landscape has changed drastically in the decades since this truism was popularized. Traditional publishing, with its gauntlets of gatekeepers, is no longer the only path to success. Many choose to self-publish, and in self-publishing, sometimes it takes money to make money. Readers, editors, cover-artists and myriad other paid contractors are often used by successful self-published authors to polish their work and attract a wider audience.

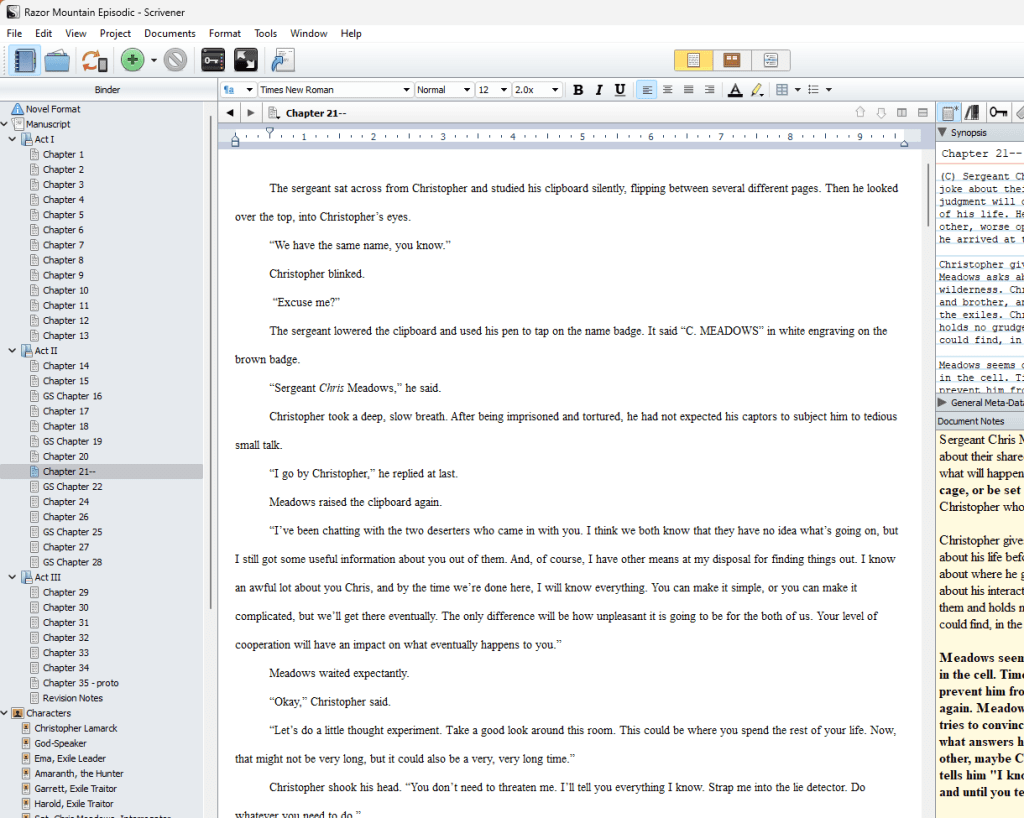

I’ll admit that I’ve always been more focused on the traditional routes to publishing, so I was even more surprised to discover that fees paid by writers have crept into the world of short fiction as well. And this isn’t even self-publishing. It is now widely considered normal for literary magazines to charge several dollars in reading fees to authors who submit short stories for consideration, even when those journals pay little or nothing upon publication.

How Did This Happen?

In reading about this topic, I’ve come across a few explanations (or excuses) for this sea change. The audience for short fiction has been shrinking for years, stolen by games and movies and social media, so it’s harder to sell magazines. Publishing has always been a hard business, and it’s getting harder. Editors need fair compensation. Too many writers are submitting, and the slush pile is unmanageable.

There is no shortage of voices, both writers and editors, who claim that submission fees are “worth it.” Fees allow more literary journals to survive, which means more short fiction is published. These journals provide a valuable service: a place for up-and-coming writers to show off their work and grow their audience.

Publishing is not a business that moves quickly or embraces technology easily. That’s why Amazon was able to take over the ecosystem from publishers that dominated for decades. However, most of these journals have finally moved online in recent years. In fact, many no longer have any print presence whatsoever.

Many of the costs of running a journal are fixed: editors and readers are needed to trawl through the never-ending slush pile of submissions. Websites have maintenance costs. But there are also costs of printing that scale with the number of issues printed. Moving online should result in some sort of savings. So why are submission fees still becoming more popular?

There’s another reason for these fees, whispered wherever authors and editors gather: Submittable.

Fees as a Service

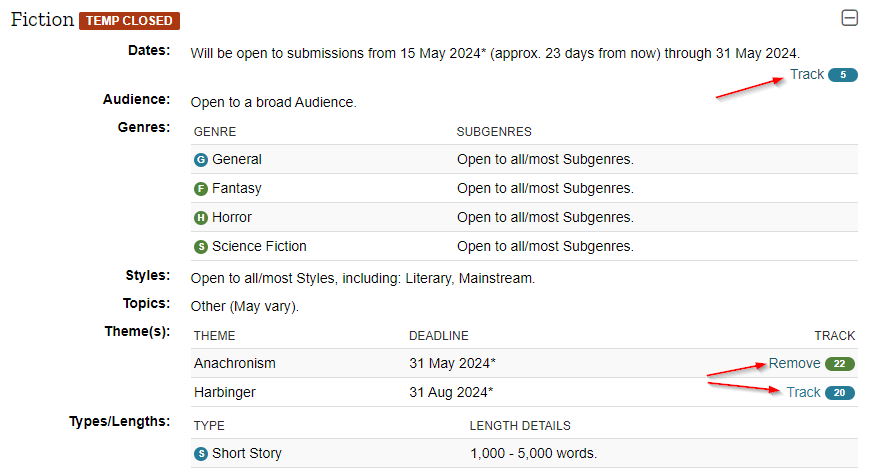

Submittable, according to its marketing, “streamlines workflows for publications of every kind, so you can get your content to more audiences, faster.”

Submittable is a private, VC-funded startup that provides software-as-a-service. I don’t think there are public numbers, but it’s likely that literary magazines are only a small part of their overall business.

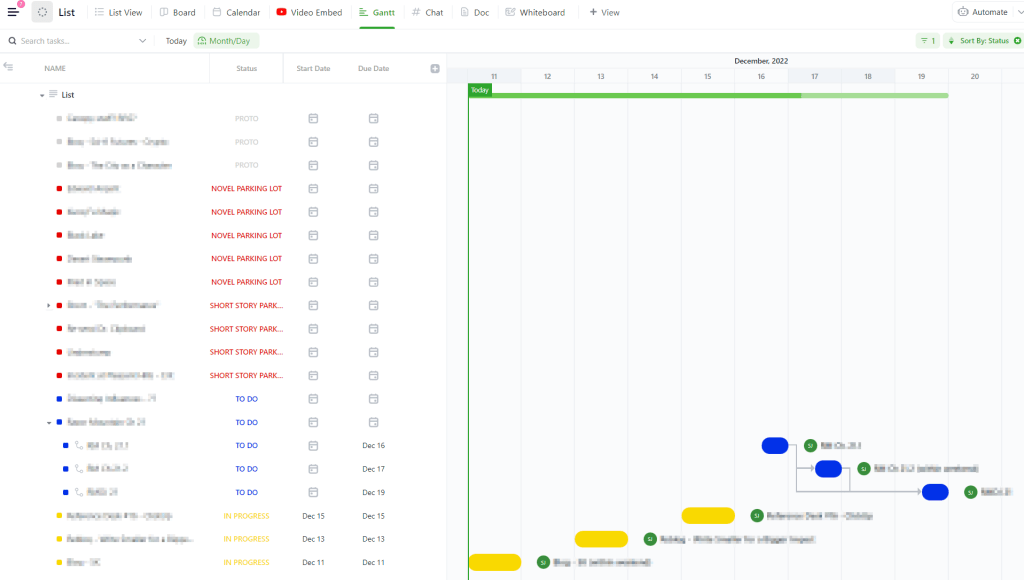

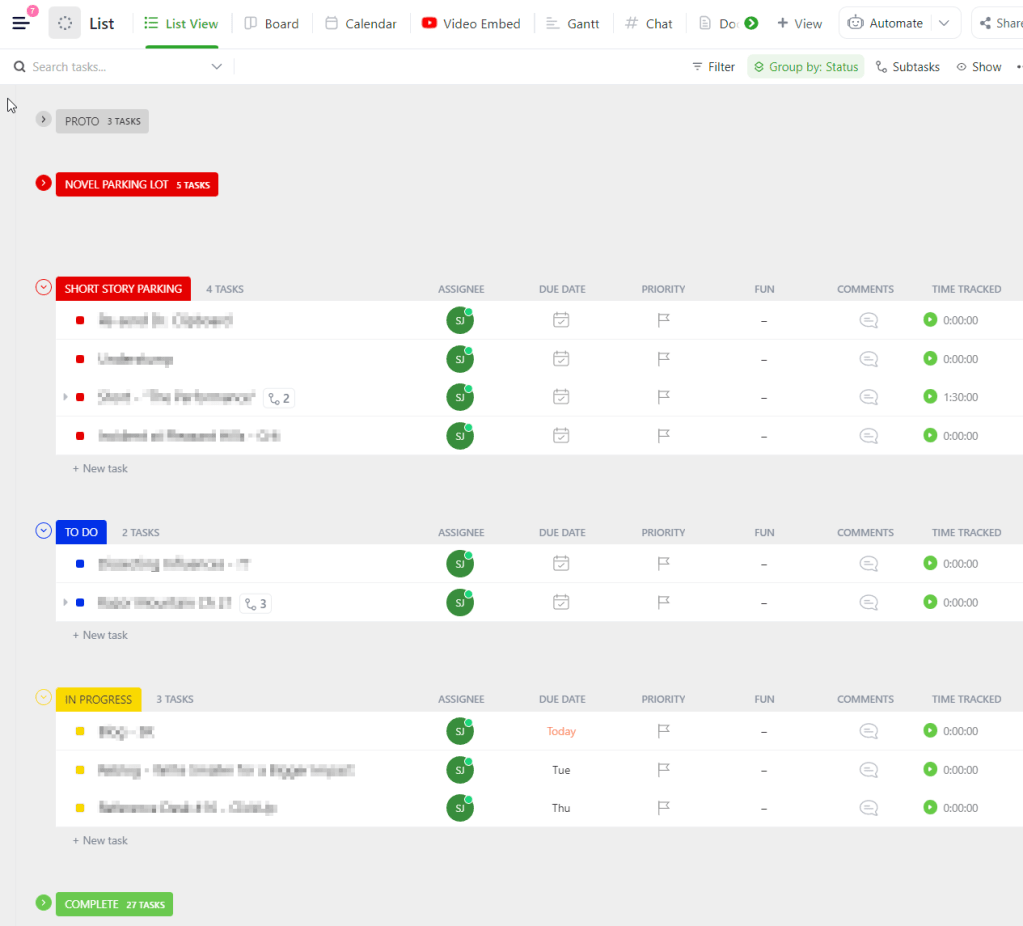

For these journals, Submittable provides a means to accept, track, and respond to electronic submissions. No more piles of mail. No more paper manuscripts. Organize the slush pile, and send responses with a few clicks.

Sounds like a great thing. Except that Submittable makes its money by charging a fee for each submission it processes. This means that more submissions cost the journal more to process. Thanks to the pressure of these fees, Submittable’s business model often becomes the journal’s business model.

Cause and Effect

I don’t find the pleas for understanding from editors particularly sympathetic. They suggest that editors consider their own difficulties more important than any hardship their writers might face. I’ve seen more than one editor suggest that it’s unreasonable for writers to be mad. After all, don’t their staff deserve to be paid a living wage? Never mind that even full-time writers often don’t make enough to get over the poverty line.

Are these editors publishing as a side-job? It’s not uncommon. But it’s still uneven treatment to suggest that their side-gig deserves pay more than the authors that actually fill their publication.

I’m even less sympathetic toward submission fees when the journal doesn’t pay upon acceptance. What other profession requires the people producing the work to pay? This only makes sense under the assumption that art doesn’t hold any real economic value.

Is it really a valuable service to show off the work of upcoming writers while costing them money? If the publication isn’t being read enough to actually make money, how effectively is it promoting these writers? There are tons of ways authors could put their own work out into the world effectively for free, so the value of a journal must be prestige a or gatekeeper that ensures quality.

Nowhere else in publishing is this considered acceptable. Authors with a book in hand are warned never to work with an agent who requires up-front fees. Agents take a cut of the actual profit as motivation to get their clients a good deal. Book publishers who charge authors up-front fees are condescendingly referred to as “vanity presses.” So what makes short fiction (and especially short literary fiction) different?

Misaligned Incentives

Publishing works best when all the incentives align with the goal of creating a good product. A publication that relies on purchases and subscriptions from readers is incentivized to provide the most satisfying product to those readers. When less of the overall budget comes from readers, the incentives change. A hypothetical magazine that makes all its money from submission fees is incentivized to maximize the number of submissions, not the number and satisfaction of readers. It wouldn’t matter if the magazine had no readers, if they could convince authors to keep submitting.

Reading fees also skew publishing even more toward the privileged, and add yet another obstacle for struggling writers. A $2-3 fee isn’t a lot, but it is an emotional, mental, and sometimes very real financial barrier that a writer must overcome to submit. Determined writers aren’t submitting a couple times. They’re submitting dozens of times, sometimes for a single story. Fees add up.

Some publications have fee-free periods, or reduced and waived fees for specific underprivileged groups. This is a good thing, because it tries to address the problem, but it only goes so far. It’s a half measure that admits there is an issue, while only offering a partial solution.

But What Are The Alternatives?

It’s not easy to run a small publication. But that doesn’t make it ethical or justified to charge writers. Writers may seem like an infinite resource, and they are often abused because it is easy to do so.

For many writers, making a living (or something closer to a living) involves diversifying their income streams. They take writing contracts or work as journalists, copy-editors and proofreaders. To survive in challenging times, publications need to also diversify and be clever about their income streams. Luckily, we live in a time where there are a lot of ways to diversify.

Patreon, Kickstarter, and other crowd-funding platforms make it possible to build a community where the people who care about what you do can contribute directly to it. Many publications crowd-fund their regular issues and kickstart anthologies or other special editions. This requires good community engagement and providing a product that people like.

I’ve seen a few publications with optional submission fees. This is another form of patronage where authors who are well-off can offset the costs for those who aren’t. This can also take the form of payment for feedback, which is sometimes a nice option for those who are looking to improve their craft and struggling to understand why they aren’t landing more stories.

Merch, ads and sponsorships are other possible avenues for funding, all with their own upsides and downsides. With all these options, it’s easy to forget the original and simplest business model for literary journals: readers paying for stories. This can take the form of subscriptions, per-issue pricing, freemium models, and a million other variations.

Dumping Submittable

When it comes to Submittable, with its problematic fees, I think there’s a straightforward way to make things better. Just stop using it.

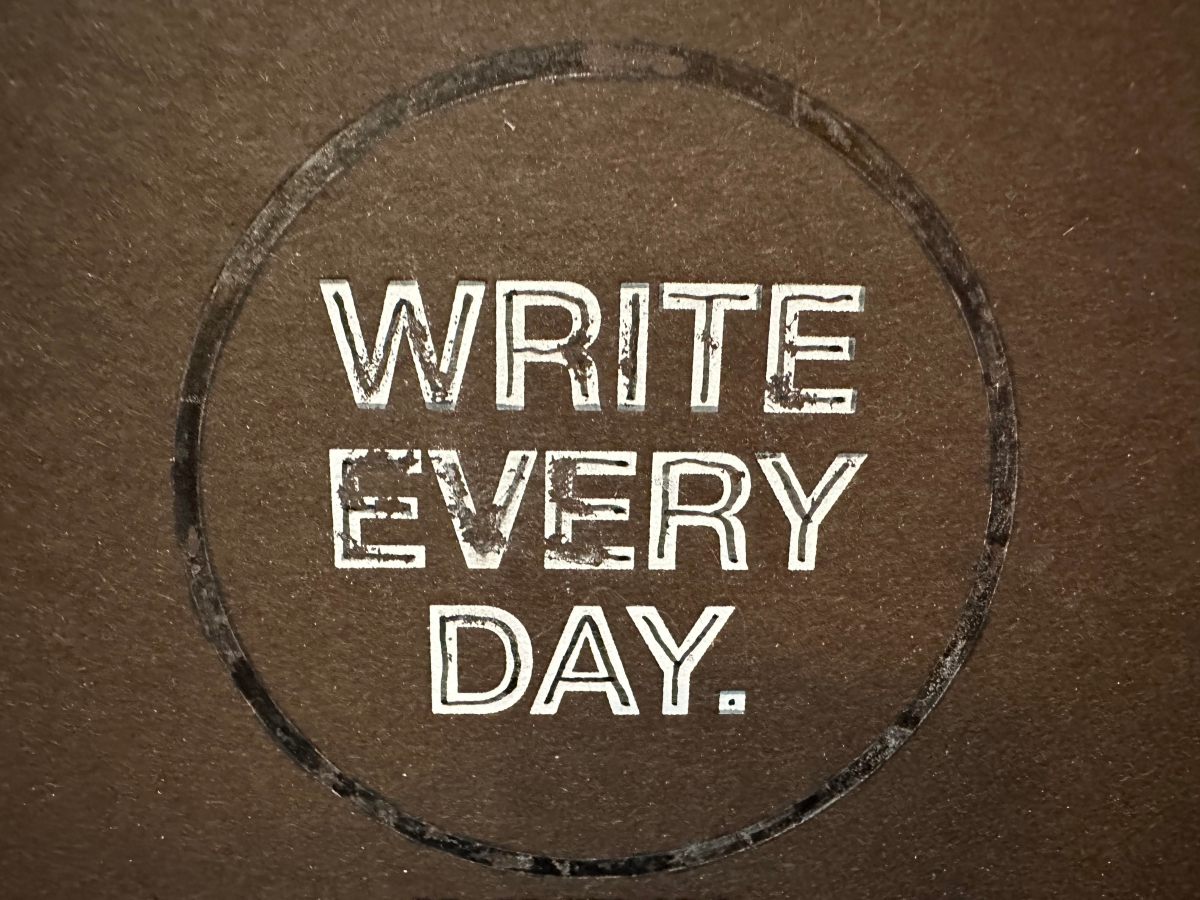

The speculative fiction (sci-fi/fantasy/horror) community is lucky to have an unusually high percentage of tech-savvy people working in it. There’s a reason why we have sites like Critters. Unlike other communities, spec-fic has pretty much completely eschewed Submittable. Instead, they’ve worked together and pooled resources to build tools like Moksha, or the Clarkesworld submission system. And none of them charge submission fees.

Don’t Settle

I come at this topic with a biased perspective. I’m a writer, and I don’t like paying fees to submit my work. But I don’t think it’s biased to say that submission fees for short fiction have a negative effect on readers, writers, and publishers. They might be the easiest solution to a hard problem, but that doesn’t make them the correct solution.

Writers shouldn’t excuse submission fees as a necessary evil. We should expect more from literary journals, even if that means these publications need to explore a creative mix of funding solutions to remain viable. Rather than accepting overpriced tools like Submittable, publications should work together on community tools that serve the community’s needs.

Writers and editors should be pursuing the same goals: a vibrant, healthy fiction ecosystem that not only produces great art, but also values that art and the writers producing it.